Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking.

Marcus Aurelius

There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.

William Shakespeare, `Hamlet´

Wisdom is nothing but a preparation of the soul, a capacity, a secret art of thinking, feeling, and breathing thoughts of unity at every moment of life.

Hermann Hesse

I must write it all out, at any cost. Writing is thinking. It is more than living, for it is being conscious of living.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh

In a recent conversation on the topic of general well-being, when the focus shifted towards mental fitness and emotional sobriety, a participant used the word `composure´, which I hadn’t heard in quite some time. It registered with me in such a manner that I decided this week to explore its meaning and the role it plays in my life.

The following quote which Steven Covey attributed to Viktor Frankl immediately came to mind: Between the stimulus and response, there is a space. And in that space lies our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom. This beautifully describes the context in which I would like to explore the phenomenon of composure.

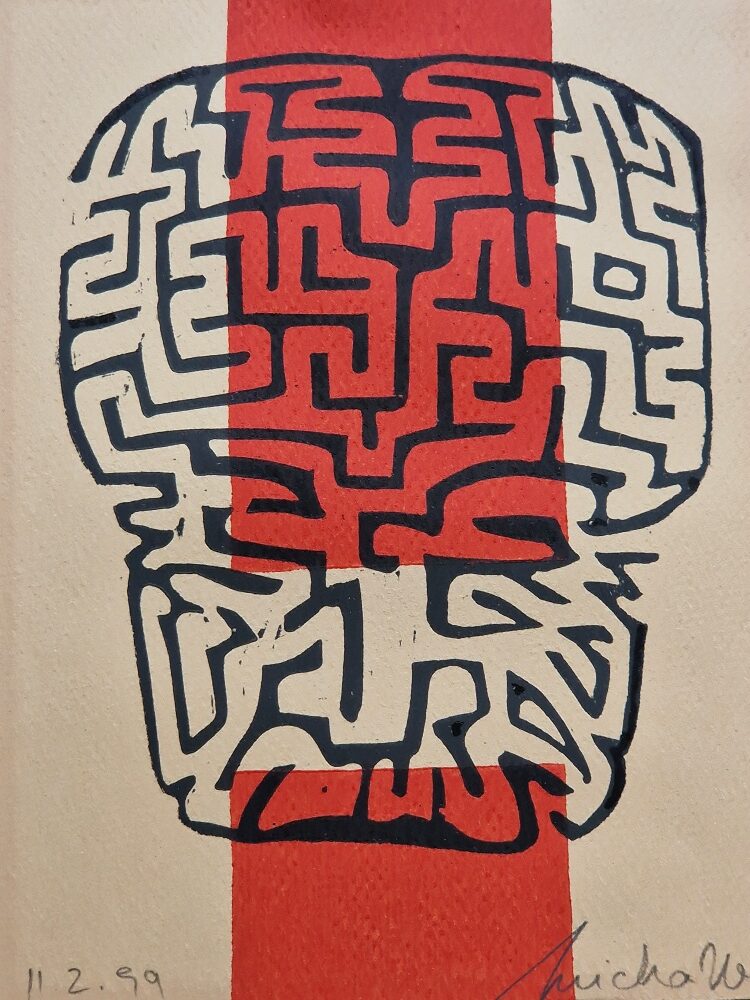

In my imagination I see a tiny crack of light between the moment the impulse registers in our brain and when we answer. The impulse may have its source in the outer world; what someone says, a fragrance, a sound, etc. Or it may even come from an internal source; our own mind, in the form of a memory, an interpretation, a thought, or an association. It may have its source in reality or in the imagination. The receiving area of the brain, the neocortex, cannot distinguish between the real and the imagined; incoming signals are simply incoming signals. They will generally invoke a reply.

The reply, depending on the width of that space, can be in the form of a reflex, a reaction, or a response.

A mental reflex, just like a physical reflex, happens before we even realise it. Some of the greatest saves in football are of this nature, the goalie as surprised as anyone that the ball had been, seemingly miraculously, tipped over the bar. In neurological terms, the impulse signal does not even make it as far as the brain. On arrival at the spinal cord, a primitive form of reply is instantly transmitted back through our physiology. The value of this seemingly instantaneous interaction, shaped by our survival drive, is that it saves time; the spared milliseconds could be the deciding factor between life and death.

On the mental plane, when we reply to impulses with a reflex, we realise so only after the fact and cannot account for how such a reply, whether physical or verbal, got formulated. The degree of activation (by the sympathetic nervous system) of our `fight or flight´ state determines how likely we are to reply in such a manner. Stress is clearly no friend of composure.

As the crack widens, the potential of reaction emerges. This moderately swift reply is also driven by the sense or belief that we are somehow threatened or in danger. An example from this past week was of a friend calling me in distress, feeling grief after hearing of the sudden death of his life-long friend. Instead of simply taking the time to embrace him in his pain, I heard myself saying how important it is to recognise and accept the mystery of life.

Afterwards, while I recognised that, in principle, this is indeed important, I also saw that my timing was way off. The most loving response in the situation would have been simply to embrace my friend in his pain and to reassure him that I would remain there for him for as long as he wished to draw strength, solace, and consolation from our encounter.

On further reflection, I discover the reason for such behaviour on my part is my wish to avoid my own pain of experiencing him in his pain. This is a characteristic of a deeply ingrained `pain avoidance strategy´ which became the cornerstone of my modus operandi in the first half of my life. Since my early forties, after having embarked on the path of recovery and emotional sobriety, I have been slowly dismantling this approach, replacing it with more awareness-driven behaviours.

As the crack between impulse and reply widens even further, we enter the realm of responding. Here the gap is sufficiently wide for the protagonist to observe what the impulsive reply might look like, identify and weigh up alternative options, and then make a conscious decision, followed by prompt action.

Fresh input might include the reflection that the relationship is more important than any particular outcome, that oftentimes simple presence is the most valuable gift we have to offer, the realisation that the `other´ is always at least ten percent right, or some other nugget of wisdom which can then inform our more aware response. This might sound long-winded, but it still happens in the blink of an eye, relatively speaking.

By understanding what happens between the stimulus and the response, and by training our `impulse/response muscle´, we can learn to better cope with everything else going on around us. Within ourselves, we can stay calm and choose the most appropriate, loving response, a response that is more conducive to producing harmony and well-being for all concerned.

As the last fifty years of neuroscientific research have shown, the neural circuits in the neocortex are malleable in development and throughout life, so that each of us acquires individual skills, abilities, personalities, and memories, as we mature.

The fact that the word `response´ is contained in the word `responsibility´ is no accident. By engaging in practices that help cultivate the gap between impulse and our answer, we learn to be more responsible for how we interact with our inner voices and the surrounding world. We become more responsible in our interactions.

The first step is awareness. This usually involves getting to know and grasp some insights which will eventually propel us towards new action. An understanding of our neural dynamics and the human nervous system are pertinent in this case. When the sympathetic nervous system is excessively activated much of the time, it can lead to burnout, exhaustion, and the inability to sleep. Breathwork can counteract this, by initiating the body’s parasympathetic response, helping us relax and heightening our conscious awareness during stressful situations. Breathwork is a well-known means of activating the parasympathetic nervous system.

While we generally think of yoga, chi gong, or tai chi, when it comes to coordinating breath and movement, this can also be practiced during any physical act such as walking, swimming, riding a bike, or even washing the dishes.

Insights, therefore, when combined with the courage to grow, lead to practice. It is by establishing and expanding the practice on a regular basis that new neural pathways are formed, strengthened, and maintained. Neuroplasticity had been established as a scientific fact by extensive empirical research. This means we know the brain can be re-wired and re-formed as we go along, with old neural pathways (ideally those no longer of service to us) withering away, to be replaced by vibrant new pathways, – hopefully associated with the new life-affirming behaviours of loving-kindness.

It is the new behaviours which initiate the rewiring, not the other way around. This explains why we cannot think our way into healing and growth. The new behaviours lead the way, whereupon the thinking gradually catches up.

What I need, then, is a daily practice which keeps me mentally fit. I have discovered a user-friendly and effective resource in the Positive Intelligence (PQ) Mental Fitness modality, developed by Shirzad Chamine and his team in San Francisco. After two years of daily practice and immersion in the insights, – as part of my training as a Certified PQ Coach, – I already feel the benefits of that gradual widening of the crack between impulse and answer.

The delivery of short body-oriented exercises throughout each day, – by means of an easy-to-use PQ App, – makes it easier to maintain regular practice over time. Just as with physical fitness, when we drop off in the practice of Mental Fitness, we regress to lower levels of fitness or, in the worst case, revert to the feeblemindedness of believing we are (the prisoners of) our own thinking. More information on the PQ modality can be found here: https://www.pq-mental-fitness.com/

Many of you have probably experienced the soothing effect of being in the presence of a person who is in a state of deep equanimity, – that balance of heart and mind, especially under stress. The experience is palpable and very powerful. Here we can see that mental energy fields are contagious. This works both ways, of course, as we often find when we walk into a family home full of tension and fear.

In cultivating Mental Fitness therefore, by widening the gap between impulse and response, we are not only doing ourselves a service; in our growing composure, we contribute to the well-being of those we encounter during our day, and perhaps even far beyond.