One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.

Carl Sagan

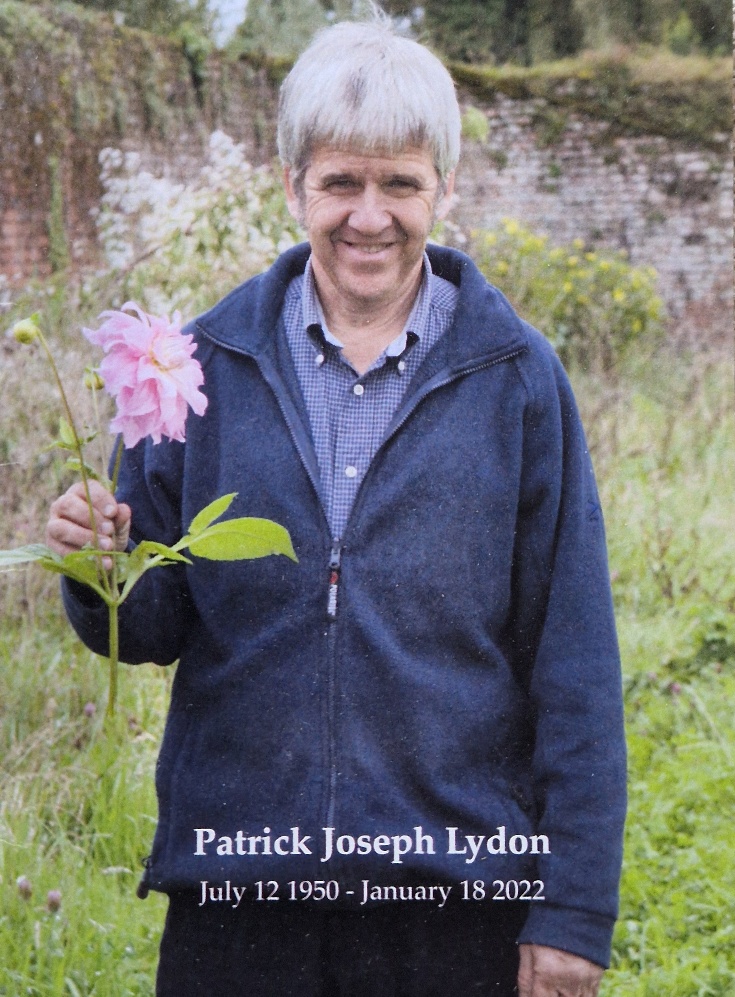

But as Patrick Lydon says in Born That Way, a film, about his life and work with people with disabilities, „Their issues are not health issues. They are who they are.“ However, it is not the intention of this film to deliver messages. If delivering messages was my intention, I would have looked for work in the postal service. My job was to make as good a film as I could with the material at my disposal, in the belief that if I could do that, any messages inherent in the material would shine through.

Éamon Little, Irish Filmmaker

Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a relationship between equals.

Pema Chödrön

Born That Way is a beautiful, reflective film portrait of a man, his vocation, and his life’s work of service to humankind. Just released in cinemas in Ireland this month, it is also a reflection on how society has changed over the recent decades.

Patrick Lydon is the main protagonist in this documentary on the evolution, expansion, and the demise of the Camphill Community model in Ireland, originally established to enable people with and without disabilities to live together in joy, harmony, and dignity.

In the film, Patrick Lydon reflects on how people with disabilities had been his teachers throughout his entire adult life. Éamon Little, the writer and director of this film, has managed to encapsulate important lessons in this moving film.

Inclusion is one of the main threads in the fabric of this story, as is the acceptance of the purity of the soul of each and every person, regardless of any damage the vessel of this soul may have suffered. In the end we are all „born that way“; this is the conclusion of the film when it comes to physical and intellectual disabilities.

I like the fact that the word „disability“ contains the word „ability“. We all have abilities in our own unique way. When we look at the spectrum of autism, for example, I can see strong traces of that in my own personality, from an intense interest in patterns unseen by others, to an uncanny agility in numerical acrobatics, to a social awkwardness which I circumvented for decades by getting intoxicated (high) which helped me feel at ease in social settings.

This is where the parallels and differences between Patrick Lydon’s vocation and mine become apparent.

A person born with Down Syndrome, also known as „trisomy 21“, has no choice in the matter. It is up to those caregivers, friends, and society as a whole to respond in a dignified, loving manner, to join and support that person in unpacking the gifts of such an extraordinary soul as life unfolds.

Like Patrick Lydon, I, too, have a vocation and strong sense of purpose. Mine revolves around addiction, its causes, and the recovery process.

No child is born an addict. Research over the past fifty years has shown, however, that the circumstances in which we are raised have a major influence on our capacity or incapacity to „live life on life’s terms“ later on.

Those, like me, whose capacity was not sufficiently developed as I approached adulthood, are inclined to turn to substances or behaviours which, while helping us to function and survive, have the effect of dulling the pain of the childhood wounds we carry.

As teenagers, we began to experiment with dope and alcohol, often progressing to other drugs or habits such as over-eating, workaholism, compulsive gambling, and porn addiction, to mention just a few of the most common ways of acting out.

Because the process of suppression can never be selective, dulling the pain implies dulling all feelings, all deep emotional stirrings. It is a high price to pay, yet we see no other option. In fact, such paths are never taken intentionally, but are rather selected, usually within the first five years of childhood, on a subconscious level, driven by our need to survive.

The dynamic is summed up well in the following ditty:

„A man takes a drink

A drink takes a drink

A drink takes a man.“

Gabor Maté, a leading medical practitioner in this field, says that „not every traumatised child becomes an addict, but I have never met an addict who has not, in some way or other, been traumatised. Ask not, „Why so much addiction?“ but rather „Why so much pain?“.“

Addiction, we could then say, is, as a coping mechanism, a perverted manifestation of a yes! to life with dire, destructive consequences, for the protagonists, their families, loved ones, and society as a whole. As Donna Martin – ground-breaking Somatic Therapist, Psoma Yoga Teacher, Hakomi Trainer and Consultant – pointed out in a Zoom workshop this week: „As children, the problem was the problem. As adults, the problem is the coping mechanisms we developed as children.“

There are similarities between the way addicts and people with physical or mental disabilities are treated by our society. Members of both cohorts would have been sent straight to one of those countless European gas chambers (some of which I have visited) less than a century ago during the brutal regime of the National Socialists.

Though today’s society is far from that level of ruthlessness, the topics of addiction and disability are still both taboos, with all the inherent consequences of denial, delusion, prejudice, and, even worse, indifference.

Neither disabilities nor addiction are primarily health issues, though our society would like to pigeon-hole them there. My experience of recovery has shown me that addiction is a societal problem. Digging deeper still, we can see that addiction, its root causes and how we handle it is, in truth, a spiritual issue.

People literally walk over the degenerated bodies of homeless addicts in the shopping precincts of our cities and towns. As they do so, laden down at this time of year with their abundance of consumer goods, their eyes transmit the frantic impassioned hope that „it will never happen to my family“.

Yet it does. And even then, the motto of „Don’t talk, don’t trust, don’t feel“ prevails. Now, however, with fentanyl and other synthetic opiates flooding our streets, schools, and homes, the issue can no longer be so easily swept under the carpet.

Go to any large city in the US and you will find armies of washed-up addicts camped out on parking lots between glittering skyscrapers of shiny steel and glass. In Europe and other regions of the world, as is often the case, we are only a few steps behind.

The difference between the dis-ability of addiction and other physical and mental disabilities is that, for addicts, there is a solution. It was formulated almost ninety years ago by the first group of alcoholics who got dry and achieved sobriety by following a practical, spiritual programme of self-actualisation now known as the Twelve Steps.

Today, there are well over a hundred twelve Step fellowships active around the world to deal specifically with particular variants of addiction. With millions of members, we all follow the same basic principles as laid out in the Twelve Steps. The compact version of this approach could be formulated as follows: „Trust the Great Spirit, clean house, help others“.

Just as we have „ability“ in the word „disability“, we have „add“ in the word „addict“. When we opt for life in recovery, we have so much to add to the ongoing evolution of our species, as we navigate this treacherous pivotal juncture of our collective development. Anyone who does not recognise the jeopardy in which we find ourselves today is either asleep or in denial (or both).

Just as the Camphill ethos prizes selfless service, the Twelve Steps encourage us to pass on to the next generation – with no strings attached – the gifts we have received which enable us to live a life of abstinence, clarity, integrity, and emotional sobriety. „In order to keep it“, we are told, „we have to give it away“.

AA and other Twelve Step fellowships are, as has been the case with Camphill, under increasing pressure from state regulatory structures to comply with the „values“ and „norms“ – in the words of Patrick Lydon, the dominant orthodoxies – of our dysfunctional society. This bamboozling comes in a variety of shapes and forms.

The Twelve Step movement is often vilified by the medical profession (not all members, by any means) and Big Pharma, as quacks who do more harm than good, or, sometimes taking a different tack, are portrayed as being totally ineffective compared to the Recovery-Industrial Complex of private rehabs and life-long medication approaches to „deal with the problem“.

In addition, we have the global „war on drugs“ which ignores the widely obvious human phenomenon of „what you resist, persists“. Declaring war on drugs is a manifestation of the widespread collective denial that prevails, again with those sitting in judgement hoping that „this cup may pass from me“.

„A miracle is a shift from fear to love“, says Marianne Williamson in her commentary on „A Course In Miracles“. Recovery is a miracle – a truth I have been experiencing over the past two decades and more. Recovery is, therefore, a shift from fear to love.

So, Patrick Lydon and this Patrick (writing this essay) both arrive at the same conclusion. The only viable approach is that of love and compassion. In line with Einstein’s comment that: „Not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts“, we need to beware of the bean-counters of the state apparatus and Big Business, who will, if allowed, stamp out any models which do not comply with the prevailing doctrine of profit and control.

Camphill in Ireland was once a vibrant movement which enhanced the lives of countless people and families. It has been mortally wounded at the hands of the prevailing dominant orthodoxies, rigidly implemented by state bodies in the name of the people these should be serving.

My hope is that „Born That Way“ will provide impetus for a much-needed public discourse as to how to reverse the onslaught of the dominant orthodoxies, redress these recent setbacks, and get back to providing a vibrant, loving model of community living which benefits all concerned.

For the Twelve Step communities, let the Camphill experience serve as a cautionary tale. Initial efforts on the part of the UK government to „certify“ Twelve Step sponsors were floated some years ago under the guise of ensuring „safeguarding“. While these initial efforts were successfully rebuffed, I would not bet the house on the absence of further attempts on the part of the state apparatus around the world to control our recovery model, our activities, and our communities.

We need to remain steadfast and vigilant in growing our communities and going about our business of Inner Work which, in my view, is the keystone of the nascent collective recovery of our species as we navigate the challenges of the 21st century.